September 11, 2003

This morning we headed out early with the camera and extra water, hoping we would make it to Qalqilia, a town on the northwestern edge of the Green Line. Our taxi driver from Zababdeh was prepared to take us as far as Tulkarem, a little over an hour's round-about ride. On the way we heard on the radio that five students from the Arab American University of Jenin had been arrested overnight and that Qalqilia was under curfew. Knowing that on-the-ground conditions can change by the moment, and that news isn't always accurate, we decided to keep going, and hope that we could get into Qalqilia.

Located in a fertile area with abundant aquifer water, Qalqilia was a major agricultural center for the West Bank. Since the completion of The Wall, however, the city has been cut off from about half of its lands and most of its wells. The Wall here has made such deep incursions into the West Bank, reaching into the illegal settlements dotting the countryside in this area, that Qalqilia is entirely surrounded by this six meter high barrier complete with watchtowers, barbed-wire-marked buffer areas, and military roads. It is a very distressing sight to see, especially imagining this huge barrier slicing through the heart of Palestine; plans show The Wall chopping the West Bank up into four cantons and other small islands (some call them ghettos) like Jericho which will be all alone, with its own wall around it.

We came to get footage of this wall, and also to visit the Qalqilia Zoo. We're trying to lure a filmmaking friend here to make a documentary on the zoo, and the town which has become like a zoo itself; so we want to take some footage there, too.

Just one of the many Israeli checkpoints that are a part of every day Palestinian life.

At Tulkarem, our Zababdeh driver dropped us off after finding another driving willing to go to the checkpoint near Qalqilia; after walking across the settler road along with other travelers, we got a car on the other side and waited along time. Apparently news of curfew has stopped a lot of people from traveling to Qalqilia today. Then we finally left, went to another roadblock, walked a bit to catch another taxi to the one entrance to Qalqilia. One by one people approached the soldiers to get permission to enter.

When it was our turn, the soldier said, "Why do you want to go to Qalqilia?"

We said we wanted to meet with the mayor (true) about children's development projects (not true, but the advice given us by a journalist).

"Are you with an NGO?"

"We work with the church."

"So you are not with a humanitarian organization."

"The church isn't humanitarian?"

"I mean you aren't with one of the official groups we accept."

"Like who?"

"The UN, the Red Cross..."

"The Red Cross is a Christian organization. So is the church."

"I know I know, but I have orders. Let me see what we can do." He left to check on permission for us to get through. "There's a bench over there in the shade, if you'd like to sit."

"Thanks." After a long wait, he came back, "Sorry, they say you can't pass."

"That's silly! We have an appointment with the mayor soon!"

"I'm sorry, Qalqilia has stricter rules than anywhere now. But if you are going to see the mayor, call him. We have very good relations with him. If he calls the District Coordinating Office, they should give you permission to pass."

"Thanks, we'll do that." We set to work on a flurry of phone calls followed by a long spell of waiting.

Periodically the soldier would come check up on us. "So where are you from?"

"Chicago. Have you been there?"

"No, I haven't traveled much. When I finish my military service I want to travel. First I'll have to work to save up enough money. But the economy is so bad now, I'm not sure if I'll be able to."

"Where do you want to go?"

"I don't know. Maybe Australia or New Zealand - someplace really far away from this mess. I'm so tired of it."

"Yeah, I bet it's pretty tough. Lots of soldiers need counseling after their service."

"Yeah, and a lot of them go traveling afterwards to places where drugs are cheap and just lose it." He then saw a truck pull up and went to talk to the driver. When he returned he said, "You know, relations here are not as bad as everyone thinks. We have really good relations with the people here. That guy's daughter is getting married next week. He comes through every day. We're like friends." Clearly a lot of Palestinians can see the young man and not just the soldier uniform; the question we wanted to ask was if the young man could see what his soldier uniform, and weapons, and machinery were doing to these people.

The 25-foot tall Wall with a guard tower.

Multilingual graffiti decorates the Wall around Qalqilya, Palestine.

Eventually, permission was granted for us to enter, so we said good-bye and headed on. A taxi took us to the municipality, where we had a very nice meeting with the mayor, who discussed the desperate situation facing his town, which in the past three years has lost the vast majority of its economic sectors. No more border-town business (as at Jalame, Israelis coming across the border to buy cheaper products); no more employment in Israel (skilled and unskilled labor was a major source of work); radically-reduced agricultural potential (cut off from valuable land and water resources); no more business from surrounding villages and towns (Qalqilia had been a major business, banking, and medical center for the area). The irony, he pointed out, was that his town has had very good relations with Israel - business and professional associations and joint projects flourished here; many people worked and maintained friendships on both sides of the border. And somehow it is this town is the one paying a higher price than the rest of the West Bank. It reminded Marthame of his visit to the Cherokee lands in northern Georgia. The tribe that tried hardest to adopt European ways, the Cherokees, were rewarded with the Trail of Tears. The mayor is afraid that the new situation facing his residents, without ways to support their families, will drive them to extremism, which never had a real foothold in Qalqilia.

After a nice interview and coffee, the mayor arranged for a driver to take us to a few places along the wall to take pictures. Marthame got out of the truck and filmed until soldiers shouted at us in Hebrew from their guard towers. The thought that they probably had snipers up there was sobering.

We moved on to the zoo. The head zoo keeper/veterinarian was very kind to give us an extended tour. The first exhibit was the box of flares, sound bombs, and used tear gas canisters that have ended up in the animals' cages since the beginning of this Intifada. Then he walked us around the surprisingly big complex.

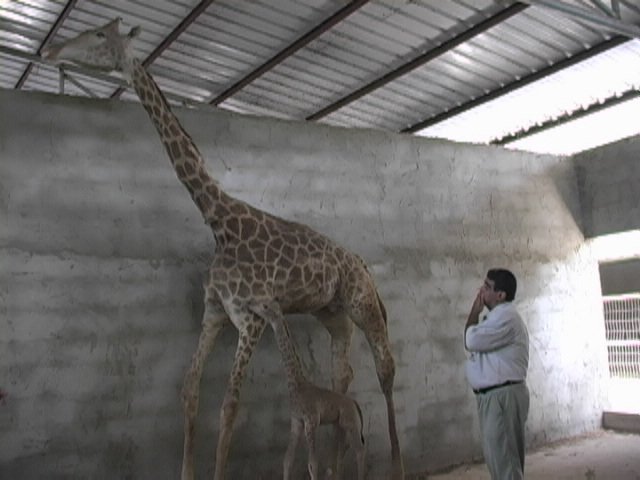

Qalqilya’s zookeeper with father and baby giraffe, casualties of an Israeli army incursion.

First up was the giraffe. Last year, when the army entered Qalqilia one night, they fired off hundreds and hundreds of rounds to announce their arrival. When gunfire passed over the giraffe area, the male got stressed out and began to run around in circles. He eventually ran into the fence and fell down. If a giraffe stays on the ground for too long, it dies because the blood pressure necessary to get blood up its long neck will kill it if not fighting gravity. A few days after the male died, the female miscarried her baby, which had only two more months (of 15) left. "We were all so sad. We'd been expecting a baby giraffe for more than a year, and now here it was dead." Our guide is also a taxidermist, and has stuffed the two, father and unborn baby giraffe, planning to open a museum portion of the zoo. "If I can't keep animals alive here, at least we can have the dead ones for people to see."

Then we saw the zebra enclosure. All three zebras died of tear gas.

"Over here, what do you see?"

"Chickens and a goose."

"Yes. I'm a zoo keeper. This is a zoo. I need zoo animals - lions, tigers, zebras -. and what do I have? Chickens."

The zookeeper feeds Ruti the hippo.

The zoo does still have more than chickens - he proudly showed us monkeys, gazelle, wolves, bears, a lion, and even gave Ruti the hippo a treat.

He has big dreams to expand, to give the animals more space than their old-timey cages offer, to acquire animals to replace the recent casualties, and to open a natural history museum section. But now, when the zoo has only a small fraction of the business it used to have, these dreams seem impossible. People from all over the West Bank and even from Israel used to visit the zoo. In fact many of our students in Zababdeh talk about visits they made to the zoo (not within the last three years, of course). Now, almost no one comes. No one can get here.

After our very nice but heartbreaking tour, we retraced our steps, checkpoint to checkpoint, back to Tulkarem, where our Zababdeh driver met up with us as we hungrily downed delicious grilled kabob sandwiches and orange soda. The trip back was fortunately uneventful, and we got home ready to shower and rest.

That evening we watched CNN's coverage of 9/11 memorials. That horrible event seems so long ago yet so oddly recent. The world has changed so much since that fateful day....