November 8, 2002

Today is our Sabbath, but we split the cost between resting and working. We left in the morning with a couple of American friends from the University and made our way to Burqin with some of our friends from Zababdeh. They are one of the families we are following in our film project. When asked "where are you from?" Palestinians often reply with their family's traditional town/city, even if they don't live there. And so our friends say they're from Burqin, even though they've lived in Zababdeh and Haifa more in the past 50 years than they have in Burqin. But Burqin is where their roots are, the setting for family lore, and what shapes their identity - and it's where they return to harvest from ancestral olive trees.

There used to be around 200 Christians in Burqin fifty years ago, but now their numbers are down to less than a hundred. Some have moved to the majority-Christian atmosphere of Zababdeh, but more have gone off to other countries in search of security and a hopeful future. It's the same story throughout Palestine.

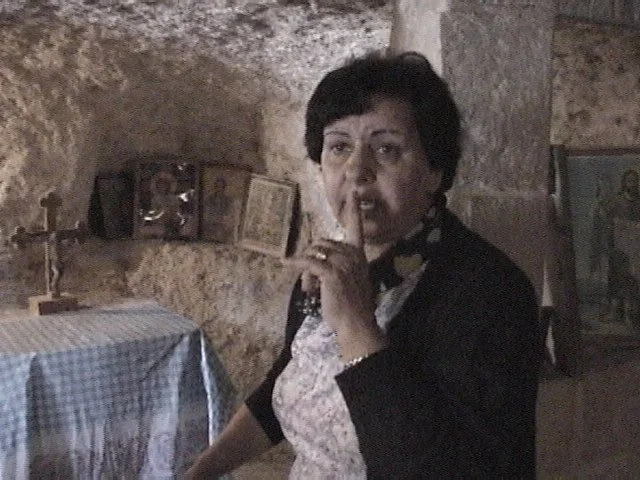

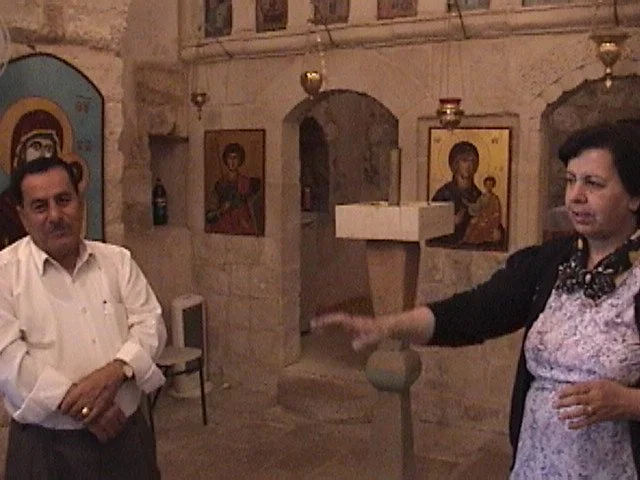

Our host, who grew up in the Burqin church, shares stories both ancient and modern.

Reliving memories of the Burqin church.

As we stood in the cool, dank cave-church, our friend's mother spoke not only about the ancient history of the church, but also personal stories and memories of hers - her grandfather the parish priest, her flight as an eight-year-old from Haifa in 1948, families fleeing with just a week's worth of clothes, living with other refugees in the church during the war, returning to Haifa twenty years later to look at their repossessed home, being recognized and jubilantly welcomed by their former Jewish neighbors...She and another of the village's faithful shared stories and memories, all colored by sweetness and sadness. That contradiction defines life here.

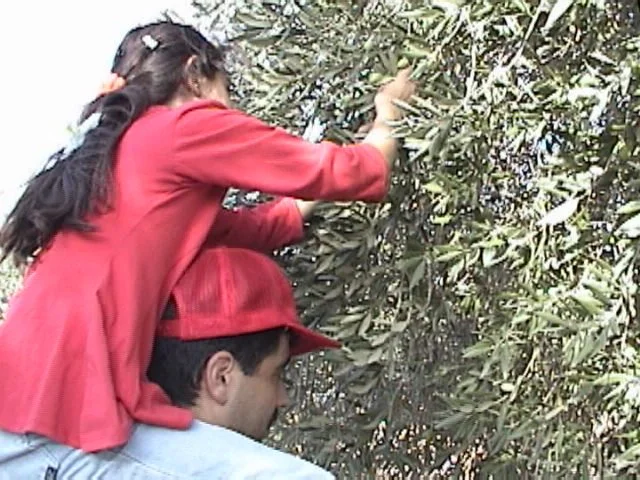

From there, we went to help harvest their olive trees. Usually, olive trees are tended on the rocky hills, and the richer flat valleys produce wheat and other crops. But our friend's grandfather decided to plant olives on his valley land, possibly because more profit could be made from oil than other crops at the time. In all, the family has three plots of land with olive trees, which is a lot of harvesting work. Now, with smaller families and most of them abroad, they have to contract out for the labor. Even so, they come every year to see how the orchards are faring, to pick a few olives to cure and eat whole, and enjoy the harvest time.

The olive harvest is a multigenerational activity.

The land is tended, the trees pruned, and the olives picked by an extended Muslim family, longtime friends of the owners. We arrived and greeted them, then excused ourselves to have a late, late breakfast under the shade of a nearby tree. "Ramadan Kareem", they said, the traditional phrase used by Arabs when the stringency of the fast restricts the usually overflowing hospitality that seems to course through the blood here. When asked if it might bother them that we were eating, our hosts replied absolutely no. "They know we are Christian so we're not fasting." Also, as we stepped aside to eat, we established a bit of private space, so in a sense we weren't really eating in public.

We've noticed cultural differences the understanding of private and public space (and time!). Rules of modesty, for example. Nobody would go out in public in shorts, but at home or in the yard or on the roof (even if clearly visible to everyone on the street) is fine, because that's private space. On a picnic with family and friends, a Muslim woman who publicly wears the veil might not wear it since the group has created private space together.

You don’t always need a ladder to pick olives.

Anyway, after our "private" breakfast, we picked olives for a while, particularly looking for the larger ones which will be used for eating rather than for pressing. The most efficient way to harvest is by hitting the branches with a stick, to make the olives fall on big plastic tarps. This is fine for olives destined to become oil, but olives to be cured and eaten whole are picked by hand to avoid bruising. Also, hitting the branches can damage the tree, but picking all olives by hand would take too long for most orchards. The harvest is hard work, but this was Elizabeth's first chance in two years, so she approached it with gusto. Marthame, however, chose to alternate between working and napping.