October 14, 2002

The group arose early and went to Gaza. Along the way, we passed the remains of Arab West Jerusalem, now scrubbed clean of its Palestinian heritage. A few old buildings stand, and terraces of Palestinian olive plantations remain, but the trees have been uprooted and replaced with evergreens, giving the impression that it is all new development. The signs Bishop Riah mentioned yesterday line the highways all the way down to the Erez crossing into the Gaza Strip.

Jabalia Refugee Camp.

Disturbing times...Before entering the Israeli checkpoint area, we noticed the turnoff for all Gaza settlements - a separate entrance, a separate system, a separate reality. It was the first time either of us have been there in a year and a half. The checkpoint remains as vacant and as daunting as ever, looking like an international border crossing but dealing with only a trickle of traffic passing through.

Mothers waiting with their children at the free MECC ob/gyn clinic.

Once through to the Palestinian side, we were met by representatives from the Middle East Council of Churches. Loading us into two vans, they escorted us around the northern edge of the Strip to see various projects in which they participate. The first was a free ob/gyn clinic, where we learned some of the realities of the medical situation these days - escalating anemia, malnutrition, pregnancy-related complications - all at much higher levels than they were two years ago. From the doctor who runs the clinic, we learned why we were not heading south at all - his half-hour commute south has turned into a 2-3 hour one, even taking as long as three days at one point because of the single checkpoint that lies beyond. Before he moved to Gaza City, he had on several occasions slept in his car on his marathon trip to work. We experienced some of that micro-division of the Gaza Strip the last time we were here. It was mind-blowing that a place where everything is so close together could be made into a place where everything is so inaccessible.

Part of the work of the vocational school is to make crutches, an item for which there is never enough supply.

The next stop was a vocational training center for the young men of the city. They are taught carpentry skills, learning to make furniture which they take home or which is sold to raise funds for the school.

The Rev. Dr. Fahed Abu-Akel shows his PCUSA Moderator cross to children at Atfaluna.

The Atfaluna Society for Deaf Children was next, which provides special education for as many of Gaza's hearing impaired children and adults as it possibly can - school classrooms, workshops, handicraft centers make up this wonderful sign of hope. In one of the classrooms, Fahed stopped to "chat" with the students. One of them was curious about the big silver cross hanging around his neck. He explained, through a sign-language interpreter, what it means in terms of his role in the church, what this large group of foreigners was doing in this place, and what message they were taking with them from this place. The child seemed satisfied in his curiosity.

Dr. Haider Abdul-Shafi, President of the Palestinian Red Crescent Society.

Our final stop before lunch was to meet with Dr. Haider Abdul-Shafi, president of the Palestinian Red Crescent Society, the man who had led the Palestinian delegation to the Madrid negotiations. Though he is well-on in years, he has a sharp mind and a clear critique - not only of the Israeli Occupation, but of the Palestinians' failure to effectively communicate their story to the rest of the world.

We gathered with the local board of the Near East Council of Churches for lunch in a restaurant along the sea. Fresh, fresh fish was the order of the day, and we chatted with a remarkable cross-section of the Gazan Christian community. They now number about 3000 in a total population of 1.3 million, and they have been dealing with the nightly bombardments that everyone else has had to cope with. Most are Greek Orthodox, though there are small Latin, Melkite, and Baptist communities here as well. The Anglican church stands on the grounds of the hospital we visited next, but there is no priest to serve it.

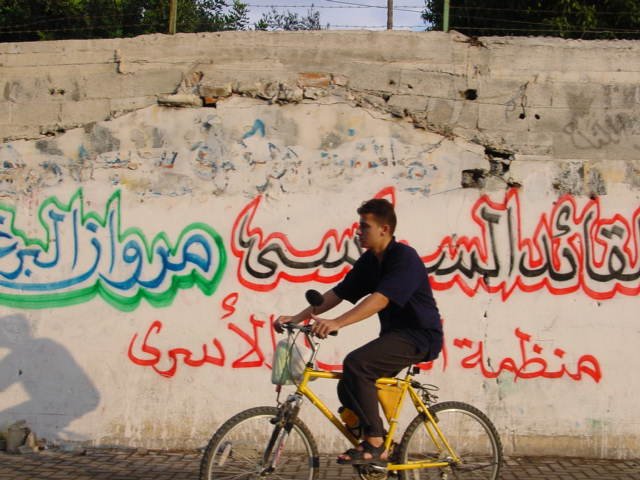

Jabalia Refugee Camp.

After sharing some messages of solidarity and prayers of perseverance, we drove through Jabalia refugee camp. The place, home to former residents of what is now suburban Tel Aviv, is a contradiction of cramped and sprawling. The streets are not paved, but covered with reddish sand. The UN schools are so overcrowded that they run in a pattern of two shifts a day. Usually, groups take an opportunity to stop and take photos (or at least visit), but our guide suggested that it wasn't wise. There is no order here, there is no Authority, and people have been living in more squalor than usual for the past two years. Every night, Apaches and F-16s fly overhead, and periodically puncture the night and Gazan buildings with rockets. If this is hell, then we are the devil's minions, we American taxpayers.

Part of Gaza’s coast along the Mediterranean Sea.

We did manage to find a relatively isolated spot and stopped long enough for Fahed to chat with three older men. Crowds of children and shabab gathered as though they rained from the sky, and some members of the group got jumpy. We soon left, but not before Fahed was able to draw out one man's opinion about the solution: 1967 borders. And this from one who would bear the greatest sacrifice of that solution: of giving up his homeland.

As we left the Gaza Strip, passing through the Israeli checkpoint, we could hear Palestinian workers heading home from their day-labor in Israel. A hopeful sign, even if these men represent a small fraction of the pre-Intifada crowds of employed workers. As they walked their long, windowless tunnel, they laughed and joked - no doubt to release the tensions of daily life. We did the same as we rode back towards Jerusalem.

Lutheran Bishop Munib Younan joined us for dinner and conversation - as we talked about the struggles they are facing, including the new demolition orders on the Greek Orthodox housing complex in Beit Sahour (to make way for a new road for settlers), he received a phone call. Another assassination had taken place in the Bethlehem area, a man tracked by cellphone. Time for him to head home while he still could.