Grandmas and Rappers

Note: This morning, we worshiped at the Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth. “Can you guess where we are?” Our guide Tamer asked us, pointing at the official map of Lod. “It’s the blank spot in the corner. According to the government, we don’t even exist.” We stood in the empty parking lot near the Mahatta area of Lod (called Lid in Arabic), a mixed city where Israeli Jews and Palestinians with Israeli citizenship live. But it is clearly a segregated city. Mahatta, home to 9000 Palestinians, doesn’t exist. It isn’t on the map. It is squeezed on all sides by the railroad, the highway, and Jewish-only neighborhoods. We literally cross the tracks – eight commuter rail lines that bisect the area’s only entrance – and enter Mahatta. In the five minutes that we stand there, trains shoot by, closing the road for four of those minutes.

This is our second day among the so-called “Arab Israelis.” In meetings with Ittijah (Union of the Arab Community Based Organisations) and Ma’an (Workers Advice Center), we learn profound statistics. 10% of Arab Israelis live in unrecognized villages, towns which don’t appear on official maps and thus receive no services – electricity, water, sewage, education. 25% are internally displaced, having fled their homes in 1948 but ended up within the borders of Israel, and yet not allowed to recoup their properties. “We are a community at risk,” Ittijah’s Director Ameer Makhoul tells us. These words don’t fully sink in until we cross over into Mahatta the next day.

On the other side of the railroad is pure squalor. Thirty percent of the Palestinian population in Lid isn’t connected to the sewage system – in Mahatta, it seems to be higher. Tamer Nafar is a local hero, as we see from the crowds of kids who follow us and shout his name. He is a hip-hop artist, quoting socially conscious rappers like Tupac and Chuck D to underscore that this is life in the Palestinian ghettoes of Israel. He looks the part, in baggy jeans, wool cap, and oversized hooded sweatshirt. His raps are punctuated with Arabic cultural references – musicians like ‘Abd al-Halim and Egyptian films are his poetic landscape. He has also become an activist, working with organizations like Shatil and Coalition of Women for Peace.

The whole scene is one of ironic contrasts. The trains carry middle and upper class suburbanites past. Nearby Ben Gurion airport, built on land belonging to the Palestinian residents of Lid, is “the face of Israel,” Tamer tells us. “Not this place.” New high-rises for Russian Jewish immigrants can be seen over the piles of Mahatta’s uncollected garbage. As for the mounting unsolved crimes in Mahatta, Tamer references Israel’s concern about the Palestinian birth rate in Israel. “For them, it’s not a problem if I die. But if I’m born, that’s a problem.”

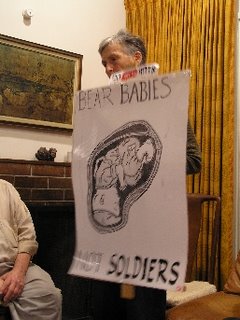

One final contrast for the day was our journey from the poverty of Lid to the suburbs of Tel Aviv. Our dinner hosts were Israeli grandmothers Dorothy Naor and Ruth Hiller of New Profile. Now in its seventh year, the group works to address the pervasive militarism in Israeli society. They offer us several examples. One Israeli mother, at the funeral of her soldier son, said, “Today, I have become an Israeli.” When a baby boy is born, his parents are complimented: “The next Chief of Staff,” their friends tell them. “So even if the Occupation ends,” Ruth tells us, “the militarism is still there.”

From the last two days, it is clear that the violence of Israel/Palestine goes far beyond the violence of Occupation and Terrorism. It is a systemic, dehumanizing violence. There is much reason for despair. But between the rappers and the grandmothers, there might just be hope.